Please put an active hyperlink to our site (www.rusnature.info) when you copy the materials from this page

Physical Geography of Northern Eurasia

Biodiversity and Productivity of Ecosystems

<<< Permafrost: Summary | Physical Geography Index | Biodiversity:

Definition and Functions >>>

Introduction

The territory of Northern Eurasia (in the borders of the former Soviet Union; FSU)

comprises one-sixth of the global land mass area, extending for 10 300 km from Kaliningrad

in the west to the easternmost tip of the Chukchi peninsula and for 4800 km from Cape

Chelyuskin in the north to the southernmost town of Kushka. The great latitudinal extent

results in the formation of various climates (modern climate was discussed above).

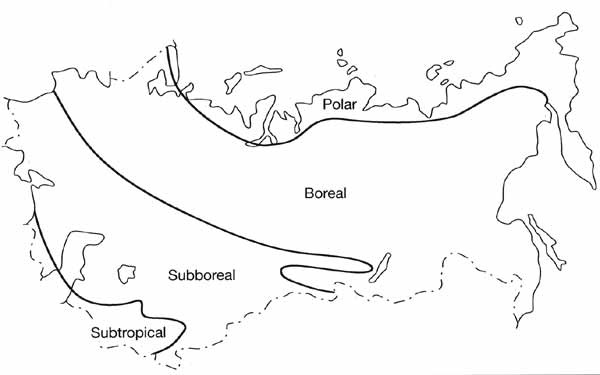

In Northern Eurasia, within the limits of the FSU, four thermal belts are distinguished

(Figure 7.1): polar, boreal, subboreal, and subtropical (Rozov and Stroganova, 1979).

Fig. 7.1 Major thermal belts of Northern Eurasia

Most of Northern Eurasia belongs to the boreal thermal belt while the subtropics occupy

a small part of the territory in Transcaucasia and in the south of Central Asia. Climatic

gradient is also a function of continentality which gives rise to four sectors, East

European, West Siberian, Central, and East Siberian, and Pacific, as well as latitudinal

zone (Rozov and Stroganova, 1979; Bazilevich et al., 1993). The complex geological history

of the territory is reflected in the heterogeneous character of its topography and

geomorphology. High mountains, reaching 7495 m above sea level (the Peak of Communism now

also known as Peak Garmo), and depressions reaching 132 m below sea level (the Karagie

depression) occur.

Consequently, the biodiversity of this vast territory is varied. Nine major biomes and

ecotones are distinguished. Every mountainous area within a belt or a sector is an

ecological entity with a sequence of altitudinal belts which may vary from one belt or

sector to another.

Until recently, much of Northern Eurasia and especially its Asian part, was practically

a pristine territory. Economic development, however, has not spared this area. The

emphasis on production of raw materials and heavy industry, extensive development, and the

low priority of environmental issues were the causes of environmental degradation and

deterioration of biodiversity (Pryde, 1991; Petersen, 1993; Feshbach, 1995). According to

estimates made in the Institute of Geography of the Russian Academy of Science, about 40

per cent of the total territory of the FSU is impacted by industry and agriculture, and

about 16 per cent is classified as seriously damaged environmentally (Kochurov, 1992).

This territory, meanwhile, provides habitats for numerous species. Seven per cent of

the global number of vascular plants, 8 per cent of mammals, 9 per cent of birds, and 2

per cent of both reptiles and amphibians occur in the FSU. Species and habitats are

preserved in nature reserves (and other types of protected areas) which represent 14 per

cent of the world's protected areas but cover as little as 1.5 per cent of the total

territory of the FSU.

In this chapter, I will focus on analysis of the basic features of current geography,

structure and functions of biodiversity in Northern Eurasia, and on productivity of

ecosystems. The chapter is mainly based on studies conducted in the FSU which, until

recently, have not been readily available elsewhere. Patterns of biodiversity, which are a

basis of any biogeographical analysis, are determined to a considerable extent by the

history of natural complexes, which provides a background for the evolution of species and

their communities.

<<< Permafrost: Summary | Physical Geography Index | Biodiversity:

Definition and Functions >>>

Contents of the Biodiversity and Productivity

of Ecosystems section:

Other sections of Physical Geography of Nortern Eurasia:

|

|