Please put an active hyperlink to our site (www.rusnature.info) when you copy the materials from this page

Biomes and Regions of Northern Eurasia

The Far East

<<< The Maritime Province | Biomes & Regions Index | Kamchatka

>>>

Sakhalin

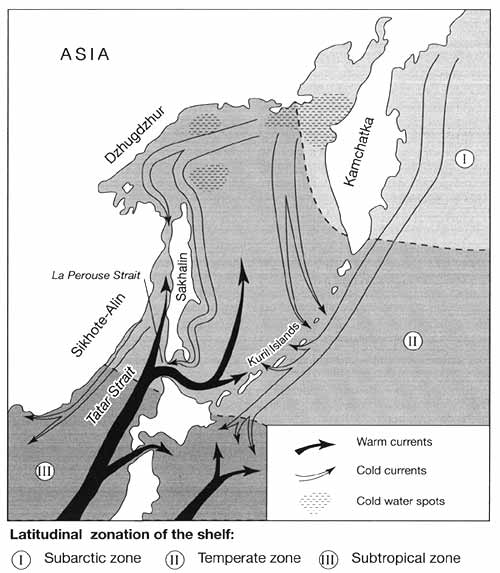

The island of Sakhalin extends along the Pacific coast for 950 km (Figure 18.1).

Fig. 18.1 A sketch map of the Far East

With an area of 76.4 thousand km2, it is Russia's largest island. In terms

of tectonics, Sakhalin is a part of the Sikhote-Alin Ч Sakhalin fold belt and is

separated from the Sikhote-Alin by the Tatar Strait trough and the West Sakhalin trough.

The formation of the Sakhalin island arc can be dated to the early Miocene since the

calcalcaline volcanic rocks of Miocene age are found in abundance in the West Sakhalin

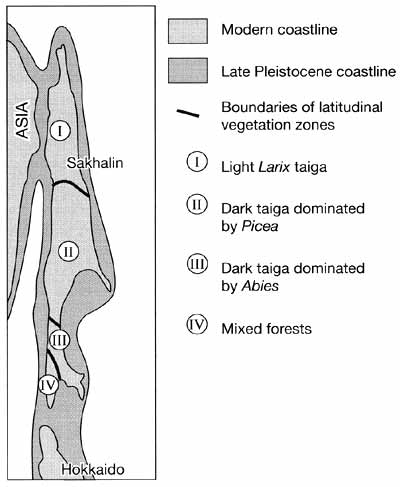

mountains (Zonenshain et al, 1990). At the end of the late Pleistocene, Sakhalin was

connected with the mainland and the island of Hokkaido by land bridges (Figure 18.3).

Fig. 18.3 Coastline and latitudinal vegetation zones in Sakhalin

A clear indication of this connection is the occurrence of dunes of aeolian origin in

the north-west of the island. The dune chains extend along the Sea of Japan coast for

about 250 km continuing into the Tatar Strait and the Sea of Okhotsk shelf (Korotky,

1993). A late glacial transgression, which began 17-18 Ka BP and proceeded rapidly at a

rate of 9 m per 1000 years, has led to its isolation (Aleksandrova, 1982). At present, an

8 km wide Tatar Strait separates Sakhalin from the mainland in the north-west while

Hokkaido is located 42 km southwards. The continuing uplift of the island (which is more

rapid in its middle part) results in high seismic activity with earthquakes reaching 8

points on the Richter scale (Geology and Mineral Resources of Japan, 1977; Leith, 1995).

Geomorphology and Environmental History

The northern sector of the island is flat while mountainous relief is characteristic of

the southern part and accounts for about 70 per cent of the total area. Although absolute

heights are low, the Sakhalin mountains have steep dissected slopes and their development

is difficult. There are three main tectonic and orographic elements extending in a

submeridional direction in the southern part (Aleksandrov, 1973):

1. The main structural feature of the island is the Central Sakhalin graben, which

extends longitudinally through the whole island and farther into Hokkaido, separating the

West Sakhalin mountains and the East Sakhalin mountains. The graben is filled with thick

(2-8 km) unconsolidated Neogene-Quaternary deposits. A chain of lowlands corresponds to

the graben of which the Tym-Poronay lowland is the largest.

2. The East Sakhalin mountains, extending from approximately 49 to 52∞N, are composed

of strongly dislocated metamorphic pre-Cretaceous rocks. Folding and thrusting occurred at

the Creataceous-Paleogene boundary. Paleogene strata overlie the nappes and the folded

structures are cut by intrusions of biotitic granites and granitodiorites with an isotopic

age of 58-66 Ma (Zonenshain et al, 1990). The ridges, broken by grabens of various ages

filled by alluvial and fluvioglacial deposits in the early Pleistocene, are distinguished

by non-structural erosional relief with numerous planation surfaces.

3. The West Sakhalin mountains formed in the late Pliocene-early Quaternary when the

rocks of the West Sakhalin trough were thrust over unconsolidated deposits of the

Tym-Poronay depression. Typical of the West Sakhalin mountains is structural denudational

relief which developed as a result of selective erosion under the neotectonic conditions

and changes in sea level. Although it is tectonic uplift which is primarily responsible

for the deep river incision, a decline in sea level of 110-130 m, which occurred during

the Pleistocene climatic minimum of 18-20 Ka BP (Korotky, 1993), contributed to the

formation of rugged topography. While absolute heights vary between 300 m and 1300 m, deep

intermontane depressions and river valleys are typical.

The plains and low hills of northern Sakhalin are composed of gently inclined folded

Neogene strata and are shaped by abrasion and denudation (Kulikov et al, 1993). The

depressions located in its central part are filled with unconsolidated Quaternary deposits

mainly of alluvial and, less often, marine origin. The lacustrine-alluvial and marine

accumulative plains occupy coastal areas. Most of the western coast has abrasional relief

with cliffs reaching 8-10 m in the north and 60-80 m in the south. At present, the western

coast has completed its abrasional-accumulative cycle and has reached a stage of dynamic

stability (Kaplin et al., 1991).

Ecology

The cold and humid climate of Sakhalin (annual precipitation ranges between 600 mm and

1200 mm; winter temperatures range between 10∞C and 24∞C below zero and summer

temperatures do not exceed 13-15∞C), resulting from monsoonal circulation and the cold

Sea of Okhotsk waters which carry floating ice even in summer, predetermines the

development of boreal landscapes across most of the island despite its location between

54∞N and 46∞N. While taiga, bogs, and coastal meadows develop in Sakhalin,

forest-steppe, steppe and semi-desert biomes occur at the same latitudes in the East

European plain. Only south-western Sakhalin has more favourable climatic conditions due to

the ameliorating influence of the warm Tsushima current which predetermines the

development of rich and distinctive vegetation. There are two main models of vegetation

zonation. According to the earlier model, which dates back to the USSR Geobotanical

Zonation Scheme published in 1947, Sakhalin belongs to the Eurasian zone of coniferous

forests which is represented by Larix forests in the north and Abies-Picea taiga in the

south. A later scheme recognizes four geobotanical entities (Figure 18.3): the light Larix

taiga, the dark taiga dominated by Picea, the dark taiga dominated by Abies, and mixed

dark-coniferous and broad-leaved deciduous forests (Geografla Sakhalinskoy oblasti, 1992).

The subzone of larch taiga is represented by swampy open woodlands formed by Larix

ochotensis with an admixture of Pinus pumila, Alnaster maximowiczii, Betula middendorfii,

and B. exilis which intermingle with shrub-lands of Pinus pumila and sphagnum bogs. Picea

forests develop in the better-drained uplands.

The dark Picea taiga formed by Picea glehnii, P. ajanensis, and Abies sachalinensis

develops in the mountainous areas of the middle Sakhalin while in the valleys forests are

formed by small-leaved deciduous species (e.g., Betula, Alnus, Salix, Populus, and

Chosenia) and locally by heat-loving broad-leaved species (e.g., Quercus mongolica, Ilex

rugosa, Ulmus ladniata, and Acer mono) (Manko, 1967; Ageenko et al., 1973). Vertical

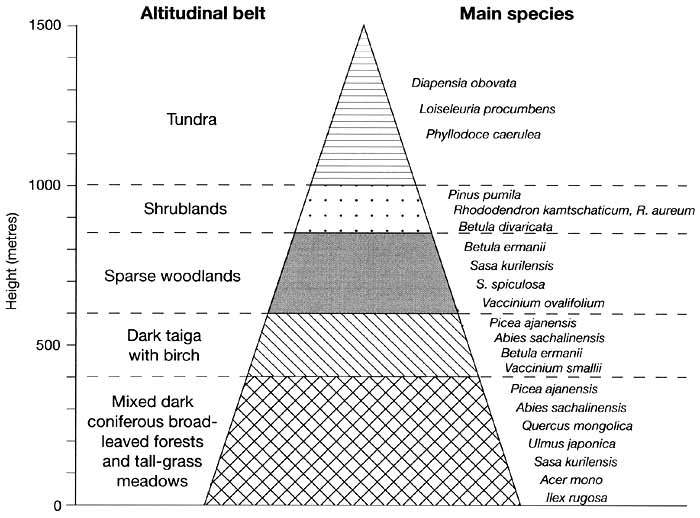

zonality is well-marked in the East Sakhalin and West Sakhalin mountains (Tolmachev, 1956;

Ogureeva, 1999), (Figure 18.4).

Fig. 18.4 A combined model of vertical vegetation zonation in the West

Sakhalin and East Sakhalin mountains. Data from Ogureeva (1999)

South of 48∞N, forests dominated by Abies sachalinensis with an admixture of Picea

ajanensis, P. glehnii, and broad-leaved species, especially Quercus mongolica, prevail.

The participation of southern species is notable and tree and shrub floras are enriched

with such species as Viburnum furcatum, Aralia schmidtii, and Ilex crenata. Bamboo (Sasa

kurilensis) forms dense undergrowth in forests as well as thick thickets in non-forested

locations. Tall-grass meadows of a simple floristic composition, comprised mainly of such

species as Polygonum sachalinensis and Cardiocrinum glehnii, are also typical of this part

of the island.

The most unusual and rich vegetation develops in the south-west of Sakhalin. There are

relatively few endemics (about a hundred out of 1500 species found on the island including

Eupatorium sachalinense, Viburnum wrightii, and Polygonum sachalinensis) because Sakhalin

became isolated from the mainland only recently. Rather, the specific character of the

vegetation is manifested in the combination of boreal and southern species, and also in

the development of gigantism, which is a very prominent feature. The mixed broad-leaved

coniferous forests contain many Manchurian and Japanese woody species, vines, and bamboo.

Such southern species as Phellodendron sachalinense, Quercus crispula, Kalopanax

septemlobus, and Toxicodendron orientale grow alongside Picea and Abies. The development

of gigantism in woody and herbaceous plants is predetermined by an optimal combination of

heat and moisture as well as the fertilizing effect of sea salts and the abundance of

microelements in the soil due to recent volcanic activity (Morozov and Belaya, 1988;

Morozov, 1994). In riparian habitats, these factors are enhanced by the high contents of

phosphorus and nitrogen in the soil which is due to the decomposition of fish that enter

the rivers to spawn and die. Plants attain lavish growth: in riparian habitats Chosenia

macrolepis reaches 25 m in height and Populus maximowiczii attains 8 m in cicumference.

Herbaceous plants, such as ferns (Struthiopterisfilicastrum), umbellates (Angelophyllium

ursinum and Heradeum barbatum), Cacalia hastata, Senecio cannabifolius, and Filipendula

kamtschatica, attain 2-3 m in height. Such vegetation communities are unique and apart

from Sakhalin occur only in the southern Kurils and northern Hokkaido. The primary

vegetation of southern Sakhalin has been extensively damaged by fellings and fires.

Secondary communities are formed by forests of Betula ermanii, bamboo thickets, and

meadows and there is no clear vertical zonation in the mountains of southern Sakhalin.

Environmental Management and Conservation

With a population of 650 000 Sakhalin remains relatively undeveloped. Coal mining, the

production of gas and oil, timber industry and fisheries are the major industrial

activities, while agricultural lands (excluding reindeer pastures) cover just above 1 per

cent of the territory. However, general statistics conceal some important regional

differences. While in northern Sakhalin reindeer herding is the main occupation outside

the rapidly growing gas and oil production, the middle and southern parts of the island

are under much greater anthropogenic pressure. The timber industry dominates middle

Sakhalin producing about 3 million m3 of wood per annum and targeting

coniferous forests which have an important protective role with regard to soil erosion and

maintenance of the healthy spawning grounds (Sakhalinskaya oblast, 1994). In many areas,

timber resources have already been exhausted and yet production continues across the

region, reducing coniferous forests by 15-19 ha a-1. These rates are

unsustainable given the lack of reforestation efforts and slow natural regeneration which

is impeded by such fast-growing species as tall grasses and bamboo. About 70 per cent of

all the Sakhalin population is concentrated in the coastal zone and plains of southern

Sakhalin which account for about 20 per cent of the total area. This region has the

longest history of development which dates back to the mid-19th century, focusing on coal

mining. Accounting for about a half of the total industrial and agricultural output, this

part of the island is under the strongest anthropogenic pressure. The development of major

offshore gas and oil reserves may prove a mixed blessing for the island. The Sakhalin

shelf contains rich deposits of high quality hydrocarbons which may provide the region

with economic and energy security and political benefits (Shelf Sakhalina, 1975; Paik,

1995). However, many environmental scientists and activists express their concern about

the potential impact of high seismic activity (Tkalin, 1993). Although environmental

impact assessment was conducted at the beginning of 1997 and the project incorporates

protective measures, doubts over safety remain given the sad history of inadequate

implementation of such measures in Russia.

<<< The Maritime Province | Biomes & Regions Index | Kamchatka

>>>

Contents of the Far East section:

Other sections of Biomes & Regions:

|

|