Please put an active hyperlink to our site (www.rusnature.info) when you copy the materials from this page

Biomes and Regions of Northern Eurasia

Lake Baikal

<<< Environmental Change in Lake Baikal

| Biomes & Regions Index | The Far

East: Introduction >>>

Environmental Threats to Lake Baikal

Human influence around Lake Baikal has been evident since at least the Neolithic period

when small populations hunted nerpa (or Baikal seal, Phoca Sibirica) on a seasonal basis

(Weber et al., 1993). Asian populations, such as the Buryats and the Mongols have also

existed around Baikal for centuries, while the first Russian settlers did not arrive until

the mid-17th century. It has only been since the 1950s, however, that environmental

concerns for the lake developed into national and international issues. These concerns

focused mainly on point source pollution (from two paper and pulp mills built in the

1960s-l 970s in the towns of Baikalsk in the southern basin, and Selenginsk on the Selenga

river), and over-fishing. By the 1980s, the campaign against these industries gathered

pace, but had now extended to include logging of the catchment and overfishing. In the

late 1980s, thousands of nerpa died from a morbil-livirus (Grachev et al., 1989), and

environmentalists suggested that the seals' immune systems had been degraded by increasing

pollution levels, including persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and heavy metals

(Galazii, 1991). Furthermore, pollution from industrial and domestic wastes, increasing

eutrophication, uncontrolled fishing, and logging of the catchment were also linked to

declines in fish growth rates, the disappearance of endemic animals, and a general influx

of more cosmopolitan flora and fauna: Lake Baikal had become an international cause

celebre (Galazii, 1991; Maddox, 1987). For example, the baikalian Coregonus is

non-migratory and its numbers were severely depleted since the 1950s due to overflshing,

but since the introduction of catch controls, populations have increased significantly

(Atlas Baikala, 1993). On the other hand, many other scientists firmly believed that

changes in the biota of the lake can be explained by natural variation (e.g., Grachev,

1991) and during the 1990s, international research programmes were established to collate

scientific evidence on the past and present environmental state of Lake Baikal (under the

auspices of BICER Ч Baikal International Centre for Ecological Research).

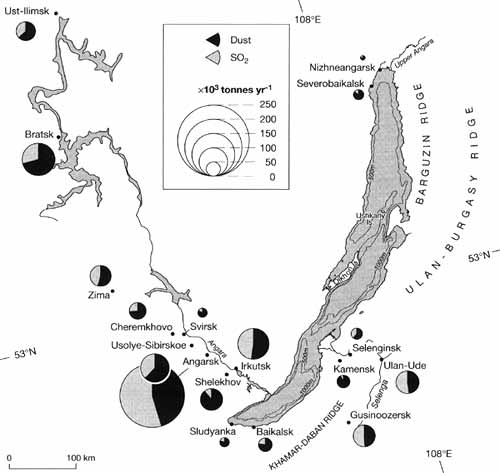

It has recently been established that pollutants indicative of fossil fuel combustion

(e.g., spheroidal carbonaceous particles, SCPs) have increased over the last 50 years:

increases were greatest in the southern basin, although small increases were also evident

in the north basin (Rose et al, 1998). These increases closely mirror levels of fossil

fuel combustion in the catchment (Figure 17.8).

Fig. 17.8 Location of principal industries in the Baikal region.

Reproduced from Rose et al. (1998)

As well as SCPs, Falkner et al. (1997) suggest that vanadium input into the lake is

increasing, while Boyle et al. (1998) provide evidence for small increases in lead

concentration in the south basin. Minor element enrichment is not as clear-cut as for

SCPs, with Vetrov and Kuznetsova (1997) even suggesting that no enrichment is occurring.

Overall, pollution levels are similar to those of Northern Hemisphere background sites,

such as the Arctic.

Using diatom analysis in surface sediments, Mackay et al. (1998) found no evidence of

the endemic flora in the lake being affected by pollution (except for localized sites such

as the shallow waters of the Selenga's delta). Increasing numbers of cosmopolitan taxa

caused by pollution is suggested by Bondarenko (1999) but more detailed monitoring of the

aquatic ecosystem is necessary. Current levels of metals in Baikal are greatest in the

southern basin (Jambers and van Grieken, 1997), although Watanabe et al. (1996) dispute

that toxic metals, such as mercury and cadmium, could cause immunosuppression in Baikal

seals because concentrations are very low.

Perhaps the greatest threat to the lake's biota, especially the nerpa, lies with

increasing levels of POPs and DDT. It has been shown that the Baikalsk mill caused

enhanced levels of persistent organic chlorines in the southern basin (Maatela et al.,

1990). Trends are complicated however: in the air above Baikal, concentrations of POPs are

similar to remote regions, again like the Arctic (e.g., Iwata et al., 1995); levels in

fish are comparable to those in the Great Lakes in North America, while concentrations in

the nerpa are similar to animals found in, for example, more polluted European waters,

such as the Caspian Sea (Kucklick et al., 1994). Bioaccumulation of organic chlorine

compounds, including DDT and PCBs, in the nerpa is thus clearly a problem, even though the

physical environment of Baikal (i.e., water, sediments) contains relatively low levels of

pollutants (Nakata et al., 1995). A direct link has not yet been made between increasing

organochlorine pollution and morbidity and mortality in the nerpa, although mechanisms

have been proposed (Nakata et al., 1995, 1997). Much more research still needs to take

place, and it is encouraging in the meantime that several local measures to reduce

pollution in the lake have already been taken, such as converting the two paper and pulp

mills into closed systems.

<<< Environmental Change in Lake Baikal

| Biomes & Regions Index | The Far

East: Introduction >>>

Contents of the Lake Baikal section:

Other sections of Biomes & Regions:

|

|