Please put an active hyperlink to our site (www.rusnature.info) when you copy the materials from this page

Biomes and Regions of Northern Eurasia

The Caucasus

<<< Introduction | Biomes & Regions Index | Modern Climate

>>>

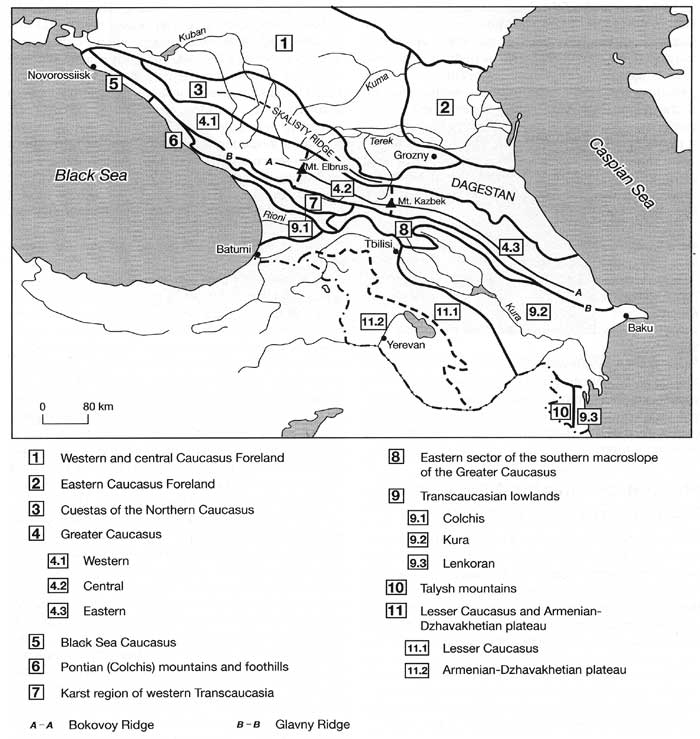

Physical Geographical Regions of the Caucasus and Transcaucasia

The main physical geographical regions of the Caucasus and Transcaucasia are shown in

Figure 15.1.

Fig. 15.1 Physical-geographical regions of the Caucasus

These include the cuesta region of the Greater Caucasus, Dagestan, the Greater

Caucasus, the Black Sea, and the Pontian Caucasus, the southern macroslope of the Greater

Caucasus, lowlands separating the Greater and the Lesser Caucasus, the Lesser Caucasus and

the Armenian-Dzhavakhetian plateau.

The cuesta region of the Greater Caucasus consists of three ridges with steep southern

or south-western and gentle north-eastern slopes running parallel to the Glavny Ridge:

Lesisty (absolute heights 800-1000 m), Pastbishny (1200-1500 m), and Skalisty (1500-3600

m). The formation of the cuestas is linked to the differential weathering of sandstones,

limestones, marls, and clays of which the area is composed. The valleys of the Kuban,

Kuma, and Terek rivers divide the cuestas into massifs which also have an asymmetrical

shape: the western slope has a character of gently sloping plateaux while the eastern

slope is very steep. Skalisty Ridge, which received its name (meaning 'rocky') from its

steep southern slope, has local elevations of 300-400 m. Extending across the Caucasus, it

plays an important part in the formation of regional climates. The northern slopes of the

cuestas (especially the Skalisty Ridge which is the highest) receive abundant

precipitation while the valleys, extending between them, and regions, located in the

rainshadow, have much drier environments. Melt water and abundant precipitation on the

northern slopes, combining with limestone and other calcareous rocks, predetermines the

widespread development of karst. Karst landforms include sinking streams, caves, and

depressions developing on the surface. The latter often exceed 100 m in depth and 200 m in

diameter. Karst plays an important role in the formation and supply of aquifers. Surface

water sinks through the limestone until it reaches impermeable clay and marl strata where

below ground reservoirs or streams develop. The water then emerges under substantial

pressure forming numerous springs in the foothills and in the highest eastern sector of

the Skalisty Ridge springs also occur in the mountainous areas (Gigineishvili, 1979). Lake

Cherik-Kel in the Cherek valley, which has a depth of 254 m and is one of the deepest

lakes in Russia, is nourished by such springs (Gigineishvili et al., 1983).

Located in the eastern Caucasus, Dagestan can be subdivided into the north-western

mountainous region, inner Dagestan, and the eastern foothills. North-western Dagestan

includes the eastern part of the Skalisty Ridge with altitudes exceeding 3000 m, and lower

chains extending along the Skalisty. The mountains intercept moisture from the Caspian and

the Eastern European plain and their northern and north-eastern slopes receive 800-900 mm

of precipitation per annum while the adjacent plains receive 400-500 mm. Similarly, the

eastern foothills and slopes receive more moisture from the Caspian than the coastal

regions occupied by semi-deserts. The original mountainous vegetation in north-western and

eastern Dagestan is deciduous forests and meadows but it has been bly altered by human

activities. As in the cuesta region, karst is well developed and there are numerous

springs and lakes of karst origin. Inner Dagestan is a mountainous region with plateaux

and ridges reaching an altitude of 2000-2700 m and valleys positioned at 600-700 m.

Surrounded by high mountains on all sides, it has a distinctly arid climate. At an

altitude of 1000 m, annual precipitation is about 500 mm, while evaporation is twice as

high (Gigineishvili, 1979). Geomorphology and exogenic processes are different from those

in the other parts of Dagestan (e.g., the development of karst is very limited) and

vegetation is dominated by xerophilous communities.

The Greater Caucasus is subdivided into western, central, and eastern sectors with the

borders corresponding to the highest summits, the Elbrus and the Kazbek. In the west, it

is flanked by the Black Sea Caucasus whose altitudes increase from 500-1000 m in the west

to 3000 m in the east. On the eastern flank, altitudes decline eastwards towards the

Caspian from about 3000 m to 500 m. The main ridges of the Greater Caucasus are the Glavny

(also known as Vodorazdelny) and the Bokovoy Ridges where the tallest summits, six of

which exceed 5000 m, are located. The Greater Caucasus forms the major climatic and

environmental divide. High altitudes and abundant precipitation provide for the

development of modern glaciation which is discussed on below. Tectonic uplift, recent

volcanic activity, Quaternary and modern glaciations and active exogenic processes have

given the Greater Caucasus its characteristic alpine landscape (Plate 15.1).

Plate 15.1 The Greater Caucasus: near the timber line (photo: courtesy

of Dr T. Galkina, The Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Science, Moscow)

It is bly dissected with a multiplicity of erosional and glacial landforms. Altitudinal

zonality in the distribution of vegetation is well developed and discussed on below. In

brief, in the western sector of the Greater Caucasus, which has large absolute heights and

a mild and humid climate, mountainous forests, and meadows are widespread. The mountains

are mainly composed of crystalline rocks and the rates of weathering and erosion are

comparatively low. In the central sector, which has the highest elevations and,

consequently a cool and humid climate, meadow ecosystems are most widespread (these become

more xerophilous in the landlocked Elbrus region) as well as nival environments. It is the

most widely glaciated area in the Caucasus and glacial landforms determine the landscape

of the high mountains. In the eastern sector, lower altitudes predetermine a lesser extent

of modern glaciation and as aridity increases, xerophilous environments become more

widespread. The region is composed mainly of shales that weather relatively easily. The

weathering and erosion rates are very high and ancient glacial forms have largely been

eroded.

The Black Sea Caucasus extends along the Black Sea coast as a system of ridges with

altitudes of 500-700 m whose height increases eastwards to the maximum altitude of 2900 m.

These are composed mainly of marl flysch and limestone but because of low humidity,

weathering rates are low. Climatic conditions and river regimes resemble those of the

Mediterranean and xerophilous vegetation dominates the area. The Pontian or Colchis

mountainous region extends further east of the Black Sea Caucasus. The division is based

on climatic differences: the Pontian Caucasus receives much more precipitation and has a

very humid climate. Under the conditions of high humidity, flysch, marls, and clays, which

compose much of the region, are easily eroded and hills have relatively low altitudes and

gentle, rolling forms. These alternate with mountainous chains with the southeastern

strike. The mountains, built of limestone, are cut by narrow river valleys and karst is

widespread.

The Gagra and Bzyby Ridges, the southern spurs of the Kondor, Svanety, and Megrel

Ridges, the Rachinsky Ridge and the Askhi plateau form the so-called karst region of

western Transcaucasia. The large spatial and vertical extent of limestone (limestone

strata exceed 2200 m in thickness) and abundant precipitation (in the western part of the

region, slopes receive 1500-2500 mm a-1 at an altitude of 1500 m) predetermine

the ubiquitous development of karst at all altitudes. The full range of karst landforms

occurs in the region. At lower altitudes, caves reaching 5 km in length, shafts exceeding

200 m in depth, and sinking streams are typical, while karren landscapes develop in the

mountains. High mountains are virtually devoid of surface runoff as water sinks through

the limestone while in the lower mountains, karst springs with high (up to 10 m3s-1)

water discharges develop (Gigineishvili, 1979). Karst landforms are often superimposed on

the glacial landforms created by the Pleistocene ice. Relict karst is widespread too. Deep

karst cavities developed in the Jurassic limestones are overlain by the Eocene clays,

testifying to the long history of karst formation in the region which dates back to the

Jurassic (Gvozdetsky, 1992). The large amount of calcium in the soil predetermines the

development of specific habitats which are drier than can be expected in this climate and

accommodate various calcicole species that are not found elsewhere. Thus, in the subalpine

and alpine meadow altitudinal belts, 33 per cent of species are endemic (Gvozdetsky,

1954). Soil cover is thin, the profiles are poorly developed and contain large amount of

rock debris. As a result, vegetation cover is often sparse. It is easily destroyed by

extensive grazing and widespread erosion follows.

The southern macroslope of the eastern Greater Caucasus comprises highlands and ridges

of predominantly medium (about 2000 m) height: the highlands of Imeretia, the Surami

Ridge, and the mountains of Southern Ossetia, Karthalinia, and Kakhetia. The ridges, which

have a meridional strike, lead away from the Glavny Ridge with the altitudes declining

southwards. Protected by the Greater Caucasus from the north, this region has a mild

climate which becomes progressively more arid eastwards as annual precipitation totals

decline from 1500 mm in the west to 600 mm in the east.

There are three main lowlands in the Caucasus: the Colchis, Kura, and Lenkoran. The

Colchis lowland (also known as Kolkhida or Rioni) and the Kura lowland, divided by the

transverse Surami Ridge, comprise the Rioni-Kura tectonic depression. The Colchis lowland

is a young accumulative plain formed during the Pliocene-Quaternary when the whole region

experienced uplift. The Miocene marine basin, which existed in its place, was filled by

sediments whose thickness reaches 700 m. At present, the Colchis lowland subsides at a

rate of 0.6 cm a-1 (Gornye strany, 1974). However, a number of rivers,

beginning in the Glavny Ridge and the mountains of Adzharia and Imeretia, drain the

Colchis lowland delivering and depositing a vast amount of alluvium at a rate exceeding

100 million m3a-1 to the coast and beyond. The Rioni is the largest

river with a length of over 300 km and a vast, 20-30 km wide, delta. The sediment

discharge by the Rioni is particularly high and intense accumulation occurs in its

estuary, filling the delta and extending the coastline (Tushinsky and Davydova, 1976).

Coastal dynamics are extremely complex in the Colchis lowland and while in some areas the

net result is the expansion of land, in other regions the coastline retreats despite the

high sediment delivery. One of the reasons for the retreat is the occurrence of numerous

submarine canyons in which alluvium is deposited (Zenkevich, 1990). The Colchis lowland

has a flat topography with altitudes gently increasing landwards. It comprises relict

river deltas and river-mouth bars and ramps, and relict alluvial deposits. Originally,

much of the lowland was swampy and, although extensive improvements have been made, swamps

still occupy large areas. The warm and moist climate of the Colchis lowland preconditions

the development of lush vegetation containing many relict species. Having survived from

the Tertiary, the vegetation in the foothills is especially rich floristically while on

the lowland itself, plant communities are less diverse because of the lowland's young age.

Little of the climax vegetation survived on the Colchis lowland with the exception of

riparian forests because it is a major agricultural region growing tea, grapes, and citrus

fruits. These and many other species were introduced in the 19th century and at present

agricultural ecosystems dominate. Of introduced plants, eucalyptus, used in amelioration

projects, is particularly widespread.

The Kura (or Kura-Araks) lowland extends between the Surami Ridge and the Caspian Sea.

Absolute altitudes decline from the west (450 m above sea level) to the east where the

delta of the Kura is located 25 m below mean sea level. The lowland is composed of marine

sediments in the east, deposited during the Quaternary transgressions of the Caspian, and

alluvium delivered by the Kura and the Araks. Protected by the Greater Caucasus from the

north and the Surami and Likhvin Ridges from the west, the Kura lowland has a dry climate

with 200-400 mm precipitation per annum. Semi-deserts and sparse arid woodlands represent

the zonal vegetation. The ground water table is close to the surface and topographic

depressions are often swampy. Wetland vegetation communities, developing in such habitats,

are represented largely by Phragmites communis and Bolboschoenus maritimus while riparian

forests develop along the Kura and the Araks.

The Lenkoran lowland is located south of the Kura lowland, extending between the

eastern foothills of the Talysh and the Caspian. It has a very warm and moist climate with

annual precipitation totals exceeding 1200 mm. Climax vegetation communities comprise many

Tertiary species but natural forests have been largely destroyed and replaced by

agricultural ecosystems. Natural ecosystems are preserved in coastal wetlands, which are

widespread in Lenkoran, and in nature reserves.

The mountainous regions of the Lesser Caucasus and the Armenian-Dzhavakhetian plateau

are located south of the Rioni-Kura depression. The Lesser Caucasus consists of a system

of mountainous ridges with altitudes of 2000-2800 m in the west and 2500-3300 m in the

east. The Armenian-Dzhavakhetian plateau comprises volcanic plateau composed of tuffs,

basaltic and andesitic lavas with absolute heights of 600-1500 m, mountainous massifs

rising to 2500-3000 m, and volcanic cones exceeding 4000 m. The two highest summits,

Ararat (5165 m) and Aragats (4095 m) are volcanic cones carrying ice caps. Both are

considered inactive although minor eruptions of the Aragats occurred in early historical

times (Nalivkin, 1973). The potassium-argon dates, obtained by Mitchell and Westaway

(1999), suggest that Quaternary volcanism began in the Lesser Caucasus and the

Armenian-Dzhavakhetian plateau before 1.1 Ma BP, and reached its peak around 0.8 Ma BP.

The climate of the region is arid with a high degree of continentality. The lack of

precipitation and the high permeability of volcanic rocks lead to meagre surface runoff

and the development of xerophilous vegetation communities, many of which have been altered

over the centuries of human activity.

<<< Introduction | Biomes & Regions Index | Modern Climate

>>>

Contents of the Caucasus section:

Other sections of Biomes & Regions:

|

|