Please put an active hyperlink to our site (www.rusnature.info) when you copy the materials from this page

Biomes and Regions of Northern Eurasia

Boreal Forests

<<< Forest-tundra and Northern Open Forests

| Biomes & Regions Index | Western

Siberian Taiga >>>

European Taiga

The European taiga is mainly composed of the dark taiga species. In the conditions of

moist climate and moderate drainage, the main forest-forming species is Picea. The

participation of Abies sibirica increases eastwards, where Larix sukaczewii and Pinus

sibirica occur in a subordinate role.

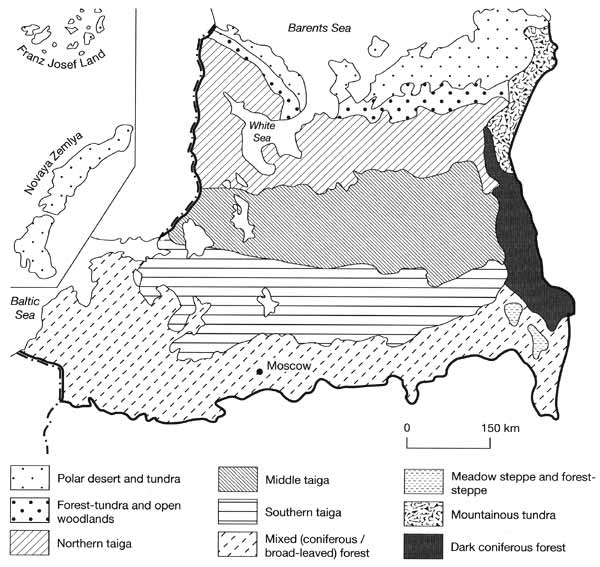

The subzone of northern taiga extends from 67∞N to 64∞N (Figure 9.3).

Fig. 9.3 Vegetation of northern European territories and the Urals.

Compiled by A. Tishkov using data from Gribova et al. (1980)

Because of the short and cold summers, with a mean July temperature of about 14∞C,

tree growth is impeded and although these are closed forests they are not dense. Light

penetrates the forest canopy allowing light-requiring plants to develop in the

undergrowth. In the west, the main species is Picea abies although large areas, especially

in Karelia, are occupied by wetlands and forests composed of Pinus sylvestris. Eastwards,

Picea abies is progressively replaced by Picea obovata, which dominates east of the

Northern Dvina. Isolated patches of Pinus sylvestris occur on sandy substrata. Siberian

species appear with Larix sukaczewii being an important admixture in the north and Abies

sibirica in the south. A characteristic of Picea forests of the northern taiga is the

ubiquitous presence of green mosses (Hylocomium splendens, Pleurozium schreberi,

Polystichum commune) and the admixture of Betula. An unusual association, Picea forests

with lichens (Piceetum cladinosum), develops on sandy and stony substrata where canopy

cover is low, between 30 per cent and 50 per cent (Agakhanyants, 1986). Productivity of

northern forests and phytomass reserves are low, on average 100 tonnes ha -1 (Bazilevich,

1993; Bazilevich and Tishkov, 1986). On the Kola peninsula, where forests develop on stony

substrata, and in the Pechora basin, where forests are often swamped, phytomass is reduced

to 30-50 tonnes ha-1. Typical of the northern taiga is a large share of dead

phytomass which may reach 30-40 per cent of the total phytomass reserve (Bazilevich, 1993;

Bazilevich and Tishkov, 1986).

The middle taiga, which extends from 64∞N to 60∞N, has a milder climate with a mean

July temperature of about 16∞C. Two main features distinguish the middle taiga from the

northern taiga: forests become notably denser and Betula disappears as an admixture to

Picea forests. The main zonal associations are Picea abies (in the west) and Picea obovata

(in the east) with Vaccinium myrtillus and green mosses. The undergrowth is virtually

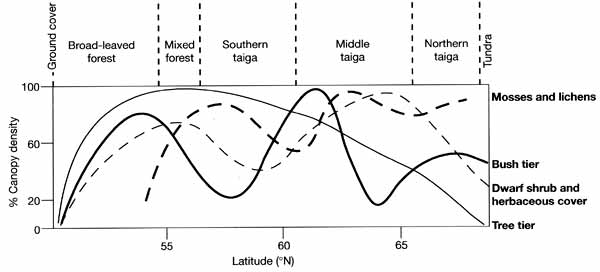

absent and the herbaceous cover is depauperate because of the lack of light (Figure 9.4).

Fig. 9.4 Spatial variability in canopy density.

Only shade-tolerant species occur, such as Linnaea borealis, Pyrola rotundifolia, and

Calamagrostis. Hilly terrain of the European middle taiga provides a variety of habitats.

Pinus sylvestris forests with green mosses develop on sandy substrata in river valleys and

on the river terraces Pinus sylvestris with Calluna vulgaris occur. Pine forests

constitute over 20 per cent of the middle taiga forests. In the south of the sub-zone, the

appearance in azonal habitats of broad-leaved tree species (Tilia cordata and Acer

platanoides) in the undergrowth and of Convallaria majalis and Aegopodium podagraria in

herbaceous cover add to the diversity of forests. Productivity of forests, phytomass

reserves, and the share of wood increases in comparison with the northern taiga. Phytomass

reserves in typical Picea forests are about 130 t ha-1 and productivity is

about 6 t ha-1 a-1 (Bazilevich, 1993). In contrast to the northern

taiga, there is little differentiation in productivity between western, central, and

eastern regions.

The southern taiga extends to approximately 57∞N. The mean July temperature of about

18∞C provides very favourable conditions for the development of forests. Picea forests

with Oxalis acetosella replace Picea-Vaccimum myrtittus forests as the main zonal

association. The role of mosses is reduced and its share in total phytomass reserve is

twice as low as in the northern and middle taiga (Bazilevich, 1993). However, the main

distinction from the middle taiga is that the composition of forest becomes more complex

as deciduous species become more abundant. The share of wood in total phytomass increases

to approximately 75 per cent (Bazilevich, 1993). Forests develop a multitier structure

with Tilia cordata, Acer platanoides, Fraxinus excelsior, and Corylus avellana appearing

in undergrowth. Where soils are rich and provide enough nutrients, deciduous broad-leaved

species (Tilia cordata, Quercus robur, Ulmus laevis, U. scarba) occur in the lower tree

tiers. These species are not widespread, the trees grow slowly and are often small.

However, it is their presence that distinguishes the southern taiga as a subzone.

Herbaceous cover becomes notably richer and species typical of deciduous forest become

more common. Pinus sylvestris stands are widespread similarly to the other subzones, and

forests composed of Alnus incana become common along the river banks and on abandoned

agricultural lands.

In European Russia, the middle and especially the southern taiga have been transformed

by human activities. This is one of the major timber-producing regions of the FSU and in

the localities where spruce stands have been cut, secondary forests composed of Betula and

Populus tremula develop. Alnus incana also spread into the southern taiga only recently

due to human influence, being almost unknown in the region three to five centuries ago.

<<< Forest-tundra and Northern Open Forests

| Biomes & Regions Index | Western

Siberian Taiga >>>

Contents of the Boreal Forests section:

Other sections of Biomes & Regions:

|

|