Please put an active hyperlink to our site (www.rusnature.info) when you copy the materials from this page

Physical Geography of Northern Eurasia

Climate at Present and in the Historical Past

<<< Climate Change within the Historical

Period | Physical Geography Index | Climate

within the Period of Instrumental Meteorological Records >>>

Documentary Sources

An array of written documentary sources is available for Northern Eurasia. These can be

broadly split into three categories: irregular information, dating back to antiquity, for

the Crimea, Central Asia, and Transcaucasia; regular and irregular records, made prior to

the mid-16th century, available for parts of the East European plain and the Baltic

region; regular and irregular records made after the Russian advance to the trans-Volga

region and Siberia in the middle 16th century. So far, not all of these sources have been

researched. The most thorough studies of historical climates using written evidence are

those by Borisenkov and Pasetsky (1983, 1988) and Lyakhov (1984a, b, 1987). These works

provide a wealth of climatic information for the East European plain during the last

thousand years.

The major original source of meteorological information for the East European plain

between the 11th and the 17th centuries are chronicles which contain abundant information

about the weather and weather-related events. These were published as a 37-volume edition

The Complete Collection of the Russian Chronicles between 1841 and 1982 in Russian and

translated into the main European languages. Chronicles were kept by the monasteries and,

although the first written records mentioning anomalous weather date back to 867, regular

recording of political, social and natural events began at the end of the 10th century

after Christianity was adopted by the Slavs and the first monasteries were established. It

continued more or less uninterrupted until the Mongol invasion in the 13th century. As the

Mongols conquered Eastern Europe, such major religious centres as Ryazan, Vladimir,

Torzhok, Kiev, and Chernigov were ravaged and chronicle-keeping in this part of Russia

declined. However, it did not stop entirely as new centres emerged in the north: in

Galich, to which chronicle-keeping moved from Kiev, and in Rostov Veliky and later Tver,

which took over from Vladimir. The two major centres, Novgorod and Pskov, remained free.

These cities became the main centres of chronicle writing as well as two monasteries, the

Solovetsky and Kirillo-Belozersky, established under the influence of the Novgorod state

in the White Sea region. Later, in the 14th and 15th centuries as Christianity was

restored and the unified Russian state began developing around Moscow, the geography of

chronicle-keeping expanded, reaching the Volga region in the 16th century and, eventually,

Tobolsk and Irkutsk in Siberia before declining in the 17th century. The most complete and

extensive records are available, therefore, for the Novgorod and Pskov regions, followed

by central Russia and northern Ukraine (Borisenkov and Pasetsky, 1983; 1988; Lyakhov,

1995a).

The major issue in using historical documentary sources for climatic reconstruction is

that of source reliability. УThe descriptions of natural phenomena in the chroniclesФ,

says Lyakhov (1995a) Уcan be considered as trustworthy because they are corroborated by

other factual information, about the scale and consequences of the event in the first

place. It should be also noted that nowhere in the chronicles is there a description of a

phenomenon which has not occurred during the period of established meteorological

observations. This points at the absence of exaggeration by the authors of the

chroniclesФ. Thus the so-called Troitsk chronicle, which documented life in the regions

of Rostov Veliky, Moscow, Tver, Ryazan, and Smolensk in the 13th and 14th centuries,

provides a description of the extremely dry summer of 1371, giving detailed information

about the failure of crops and widespread forest and peat fires. As Borisenkov and

Pasetsky (1983) point out, this description closely resembles the extreme drought of 1972

and its consequences. Usually, weather-related information given in a chronicle is

corroborated by a description of similar events in other contemporaneous chronicles. While

providing detailed descriptions of weather and often giving the exact date and time of the

events, most chronicles remained free of mystical comments about the nature and origin of

the described events. The Novgorod chronicles are especially known for their informative

and objective style.

Monastic chronicles declined in the 17th century. The main regular written sources of

meteorological and weather-related information for the period between the 17th and the

19th centuries are various types of governmental documentation. These encompass the whole

of the Russian state which extended from Poland and Finland in the west to the Pacific in

the east. Regular records and reports, which included weather and weather-related

information, were made not only in European Russia but also in the settled regions of

Siberia. Among the earliest of these documents are records kept by the Kremlin Guards in

Moscow under the order of Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich. The records, which encompass the

period between 1657 and 1675, depict the weather with great precision, providing both

qualitative descriptions and exact timing. Lyakhov (1995a) gives an example of such a

record: УYear 7165 (1657 according to the modern calendar), 4 February, Wednesday. The

day was warm and windy; it started snowing half an hour before midnight and was snowing

until the fifth hour of the night and it was warm during the nightФ. In 1696, Peter the

Great issued an order to the Navy to keep weather records as a part of ship journals. The

records were made six times per day and included wind direction, descriptive

characteristics of wind speed (i.e., strong or stormy), cloudiness, descriptive

characteristics of temperature, precipitation and its nature, visibility, and weather

phenomena (i.e., fog or thunderstorms together with the exact timing of events). These

observations provide valuable information about the weather in the Baltic, White, and

Barents Seas, the Caspian and the Sea of Azov, and the Pacific Seas. A number of ships

were guard vessels and, remaining at the same position, served as 'weather vessels'. These

were numerous in the Baltic and in 1720 five guard vessels were dispatched in the Gulf of

Finland alone (Borisenkov and Pasetsky, 1983; Lyakhov, 1995a). In addition to the regular

weather documentation, there are numerous personal diaries and reports by expeditions

which actively explored the Arctic regions, Siberia, and the Pacific. Tax records,

manorial books, and records of crop prices provide another source of data. While manorial

records give phenological information and dates and conditions of harvests which can be

correlated with weather conditions, tax and price records are a more ambiguous source of

climatic data because they depend on political, social, and economic factors as well as on

quality and quantity of harvest. Likewise, poor harvests and famines are not always caused

by the unfavourable weather.

Weather information is abundant in the written historical documents but its utilization

is difficult. Although (and sometimes if) the observers and recorders of information were

truthful and objective by the standards of the time, their standards, however high, are

incompatible with the rigour of contemporary meteorological observations. Descriptions

rely on second-hand information and, with the exception of the more recent weather

diaries, it is the chronicle or diary-keeper who selects information. Data derived from

the written historical documents are, therefore, subjective in terms of both inclusivity

and observing standards. Weather phenomena were chronicled in greater detail during the

military campaigns or political events. Thus, the anomalously dry summer of 1060 and cold

winter of 1067 are described in the Kiev chronicles in the context of military actions. No

climatic extremes were registered between 1025 and 1058 although it is known that these

were frequent both in Western Europe and Byzantium (Borisenkov and Pasetsky, 1983). Was it

because of climatic stability on the East European plain or because records were more

sporadic during the peaceful time? Likewise, following numerous reports of extreme weather

in 1230, records of hazardous weather were few during the 1230s and 1240s (Borisenkov and

Pasetsky, 1983). This period is known as climatically stable in Western Europe but another

factor, the devastation of monasteries by the Mongols, could be a reason for the declining

number of reports in Russia. Not only did the contemporaneous observers have a different

perception of events, but their criteria could be and most likely were different from the

modern ones. Thus, while some information can be interpreted in unambiguous ways (e.g.,

freezing rivers imply subzero temperatures), reports of severe winters when people and

domestic stock were freezing to death are difficult to quantify as the perception of

severity might have changed or did change as well as quality of housing and clothes.

Undoubtedly, careful and cautious interpretation of historical documents is required.

Ideally, such interpretations should be integrated with information obtained from other

proxy sources.

There are three main approaches to the utilization of historical data. First,

short-term climatic anomalies, such as drought or floods, can be catalogued. Such

information is useful even when fragmented because it provides insight into variability of

extreme weather events. Climatic instability, expressed in the increasing frequency of

weather extremes, is seen as an indicator of changing climate and such information is

particularly useful in the context of the global warming debate. Second, the absolute

trends of climate change can be determined by categorizing time periods (usually decades

or 30-year periods) as warmer or colder and wetter or drier than the present climate.

Third, the established qualitative characteristics can be quantified as temperature and

precipitation time series. The first two tasks can be accomplished through the direct

examination of historical evidence. Thus catalogues of extreme weather events between the

11th and 19th centuries have been compiled by Borisenkov and Pasetsky (1983, 1988) for the

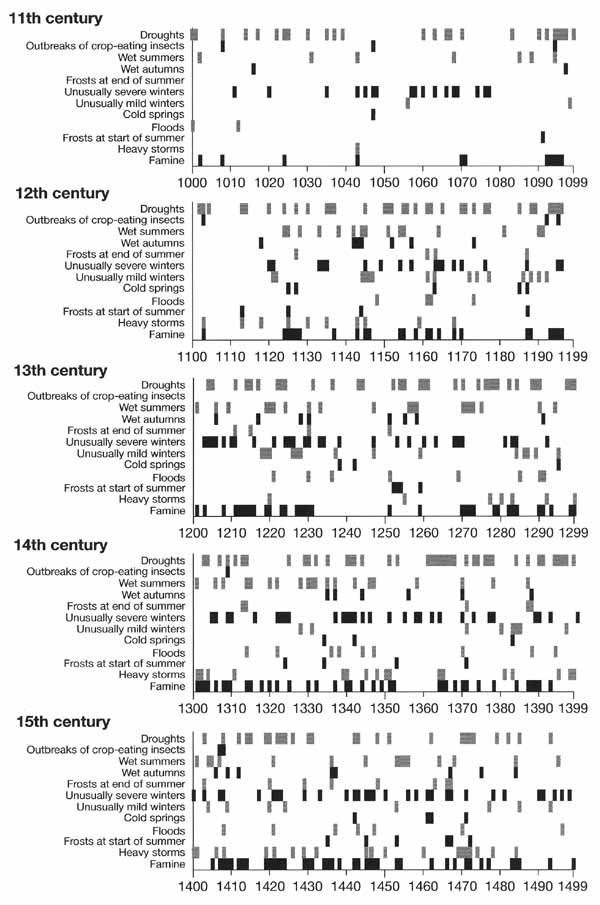

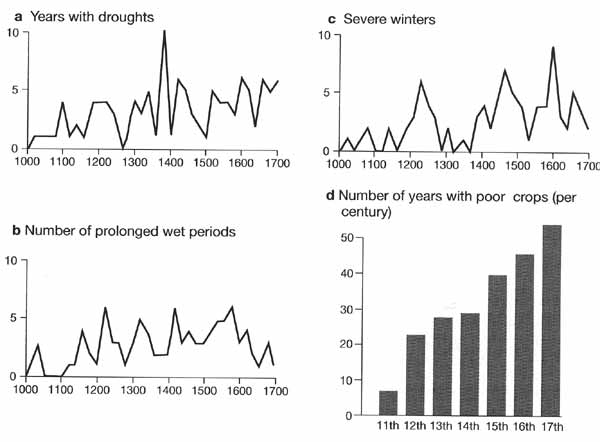

East European plain. These results are given in Figures 3.14 and 3.15.

Fig. 3.14 Anomalous weather in central European Russia and the northern

Ukraine between the 11th and the 15th centuries.

Compiled by M. Shahgedanova using data from Borisenkov and Pasetsky (1983)

Fig. 3.15 Running 20 year mean frequency of weather extremes and number

of years with poor crops.

Modified from Borisenkov and Pasetsky (1983)

Lyakhov (1984a, b; 1987) has produced seasonal chronologies in which each winter,

spring, summer, and autumn between the early 11th and the late 20th century is given a

qualitative characteristic. Quantification of historical information is the most

challenging task. Methodologies have been developed that make use of modern meteorological

data to reconstruct climatic characteristics of the past. For example, droughts or severe

frosts, reported in historical documents, can be interpreted in terms of weather types for

which modern average temperatures and precipitation totals are known. The frequency of

reconstructed weather types can be then used to determine approximate seasonal temperature

and precipitation. Another approach is to link frequency of the extremely cold (warm) and

wet (dry) seasons during a 30-year period with the 30-year temperature or precipitation

climatologies. Usually there is a close correlation between the means and the extremes

(Lyakhov, 1995a). In both methods, precipitation is more difficult to quantify than

temperature because of its strong spatial variability. The reliance on modern data

inevitably leads to the uncertainty in reconstructions as magnitudes of anomalies might

have changed. To enhance credibility of these reconstructions, other corroborative

information is used such as historical phenological or hydrological data. Using these

methods, Lyakhov (1995b) produced time series of temperature and precipitation extending

to the beginning of the 13th century.

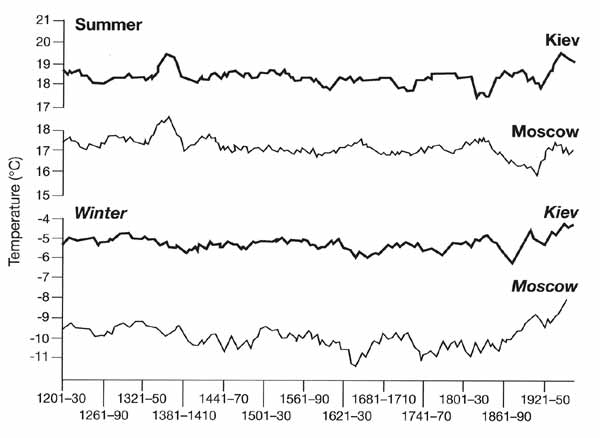

Anomalously cold or warm seasons and mean temperatures for 30-year periods between 1201

and 1980 in Moscow and Kiev are given in Figure 3.16.

Fig. 3.16 Running 30 year means of temperatures in Moscow and Kiev

during the historical period.

Modified from Lyakhov (1995b)

Temperature chronologies are broadly consistent with those for Central and Western

Europe (Hughes and Diaz, 1994; Lamb, 1995). As elsewhere, mild winters and dry summers

were characteristic of the time which is known as the medieval climatic optimum. The 11th

century chronicles report relatively few severe winters and almost no May frosts. By

contrast, reports of droughts are frequent and the particularly devastating drought of

1060 is described in a document concerned exclusively with the drought and its

consequences. The heat and dryness of the summers were responsible for the plagues of

locusts which at times spread over vast areas, occasionally reaching as far north as

Novgorod. Another social and economic consequence of droughts was frequent fires which

devastated major cities. Reports of climatic extremes, became more frequent in the 12th

century, indicating the end of the most clement period of the medieval climatic optimum.

In addition to previously reported droughts, there are records of late spring and late

summer frosts, storms, and floods. Thus, in 1143 and 1145, wet weather that lasted from

August to December caused extensive famine in Novgorod. For the first time ever,

chronicles report frosts and snowfalls in June. Characteristic of the 12th century, is the

alternation of extremely severe and extremely warm winters. This instability continued

into the early 13th century which Borisenkov and Pasetsky (1983, 1988) describe as one of

the most climatically unstable periods in history. During the first third of the century,

there were seventeen years of famine caused by climatic hazards including famines which

lasted for a few consecutive years such as in 1214-16 and 1230-3. These famines affected

the north-east (i.e., Vladimir and Suzdal) particularly badly, leading to grave social

effects and dramatic population decrease. However, the subsequent forty years were notably

quiescent. Although chronicle-keeping declined during this period, the continuing

chronicles reported solar and moon eclipses and northern lights but not hazardous weather.

The last two decades of the 13th century marked the onset of yet another climatically

unstable period which continued throughout the 14th century. The record number of droughts

was observed and these alternated with equally damaging cold and wet summers (Figure

3.15).

However, despite the increasing instability, the climate remained mild and not until

the end of the 14th century did severe winters and cold autumns and springs become

prominent. Lyakhov (1995b) estimated that in the 13th and 14th centuries, winter

temperatures were just below the current norm while in the following centuries winter

temperatures were 2-3 ∞C below the current norm. While Vikings established settlements in

Greenland and Iceland, the Slavs settled the Arctic coast, reaching as far north-east as

Novaya Zemlya, the existence of which was first reported in the 13th century. The

deterioration of climate, known as the Little Ice Age, began at the end of the 14th

century and continued until the end of the 19th century (Grove, 1988; Bradley and Jones,

1992). Although climate declined across the Eastern European plain, the biggest change

initially occurred north of Moscow. The climatic reverse involved both, severe winters and

cold and wet summers alternating with droughts and it is this instability that affected

the economy more than the increasing severity of the winters. In the 15th century,

famines, caused primarily by wet and cold summers, occurred for forty years in the Moscow,

Novgorod, and Pskov regions. However, it was the winter temperatures that displayed the

greatest anomalies (Figure 3.16). The severity of winters manifested itself through the

changing ice conditions in the Baltic, in the northern seas and even the Black Sea.

Koslowski and Glazer (1995, 1999) reconstructed sea ice conditions in the Baltic between

1501 and 1995 and showed that both extent and duration of sea ice between the 1550s and

the 1860s were considerably higher than now. By contrast, the growth of sea ice in the

Arctic was delayed until the second half of the 17th century and while western and central

parts of European Russia experienced extremely unstable and increasingly severe climate,

weather in the north was comparatively mild. However, in the 17th century the climate in

Eurasia became almost universally cold, affecting the Arctic Seas, all of the East

European plain, Crimea, and Transcaucasia and it was not until the second half of the 19th

century that amelioration of climate occurred (Borisenkov, 1992). Discussion of the

regional aspects of climate change in the subsequent chapters of this volume confirms the

continental scale of the Little Ice Age. However, few cold or warm decades appear to have

been synchronous. Documentary evidence became plentiful in the 16th century encompassing

not only the East European plain but also Siberia and the Far East. Much of these sources

have not been researched.

<<< Climate Change within the Historical

Period | Physical Geography Index | Climate

within the Period of Instrumental Meteorological Records >>>

|