Please put an active hyperlink to our site (www.rusnature.info) when you copy the materials from this page

Physical Geography of Northern Eurasia

Climatic Change and the Development of Landscapes

The Development of the Hydrographic Network of Northern Eurasia

<<< The Evolution of River Valleys in the

Quaternary | Physical Geography Index | Closed Inland Basins >>>

The Evolution of Areas of Internal Drainage

Shallow epicontinental seas and lakes covered a considerable area in Central Asia until

the Neogene. Most of the area became dryland in the Miocene during the uplift of the

mountains, although geological evidence shows that a relict brackish-water lake covering

much of the Turkmenian lowlands and the Aral basin, existed. The lake is believed to have

existed until the late Pliocene and became connected with the Caspian during the

Akchagylian transgression (Nikolaev, 1965). The development of an arid climate in the

region dates back to at least the early Pliocene when wind erosion, fostered by sparse

vegetation, and the loose deposits created large basins which were occasionally occupied

by pluvial lakes or sea water (Fedorovich, 1975).

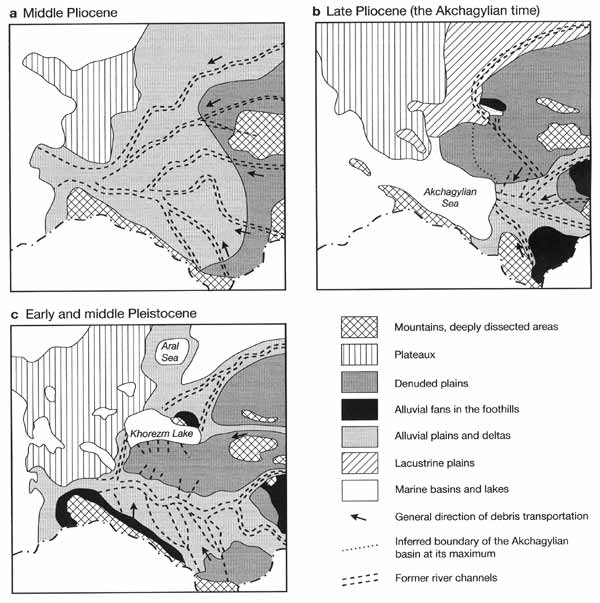

The rising mountains of the Pamir and Tien-Shan received ample rainfall, which fed

large rivers. Their sediments were deposited in abundance in the foothills and on the

plains. Consequently, an alluvial plain formed in the Miocene extending from the western

Kyzylkum to northern Karakum. It consists of sand and clay about 80 m thick. The

sedimentary composition suggests a fluvial origin from the ancient Amudarya. Other large

rivers, which drained the northern and western Tien-Shan, also transported large volumes

of alluvium and deposited fans (or inner deltas) in the foothills or reached some enclosed

basins. Later, the northern Karakum experienced uplift and the area of alluviation shifted

further south (Figure 2.6). The time of the Akchagylian transgression of the Caspian in

the late Pliocene featured an increase in moisture supply and lower evaporation. Rivers,

originating in the mountains, reached closed basins on the plain and formed lakes.

Fig. 2.6 Paleogeography of the Central Asian plains in the Pliocene and

Pleistocene. After Gorelov et al. (1989)

A complicated system of ancient Tertiary valleys exists in Central Kazakhstan where

more than three generations of valleys were identified (Svarichevskaya and Kushev, 1975).

A relatively high moisture supply was also typical of the Eopleistocene and the

presence of water bodies in many depressions, which had been filled during the

Akchagylian. One such lake existed in the Sarykamysh basin. It possibly received water

from the Amudarya and was about 70-80 m above mean sea level (a.s.l.). Another lake was

formed by the Syrdarya in the Mynbulak depression in the Kyzylkum. It has been established

that isolated enclosed lakes existed in the deepest western trough of the Aral basin (Kes

et al., 1993).

The Pleistocene was marked by progressive aridization, which eliminated the perennial

streams on the plains of Central Asia, and glaciers became the only source of runoff. The

Amudarya (which was flowing westwards), Murgab, and Tedjen brought and deposited large

volumes of sediment on the plain which accounted for the instability and frequent

migrations of the channels. Fedorovich (1975) suggested that in the early Pleistocene a

distributary of the Amudarya deviated to the north and flowed into the Sarykamysh basin

through the Upper Uzboy. Other rivers, originating in the mountains, discharged into

lakes, which were either long-term or periodically reappearing features. The Amudarya

turned northward towards the Aral Sea at the end of the middle to the beginning of the

late Pleistocene. This can be at least partly attributed to the fact that its former

channel was completely blocked by alluvium (Markov, 1965). During the early and middle

Pleistocene, the Syrdarya migrated across the northern Kyzulkum west of its modern

channel. During the Khazar transgression of the Caspian Sea, presumably marked by higher

rainfall, the river formed extensive though shallow lakes centred at about 46∞N, 68∞W

where the Chu and the Sarysu rivers joined it.

In the late Pleistocene and the Holocene, the Amudarya valley was stable in the middle

course while in the lower reaches it was constantly migrating. The river mouth moved from

the Aral basin to the Sarykamysh and back. As a result, three deltas were formed: the

first, located east of the present mouth, the second at the Sarykamysh, and a third

between both. When the river discharged into the Sarykamysh, the lake overflowed and the

water surplus discharged through the Uzboy (Fedorovich, 1975; Kes et al, 1993). The

Amudarya repeatedly emptied into the Sarykamysh, the last such event being about 800 years

ago.

<<< The Evolution of River Valleys in the

Quaternary | Physical Geography Index | Closed Inland Basins >>>

|