Please put an active hyperlink to our site (www.rusnature.info) when you copy the materials from this page

Environmental problems of Northern Eurasia

Nature Protection and Conservation

<<< Restoration of Primary Vegetation

in Damaged Ecosystems | Environmental Problems Index | International Conventions >>>

State of Biodiversity and Conservation

Flora

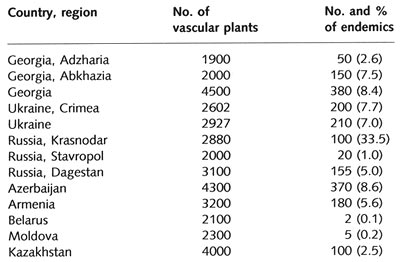

The flora of Northern Eurasia contains over 20 000 species of vascular plants. There

are about 11 000 species in Russia. Although much smaller, Tadzhikistan and Georgia

contain 5000 and 4500 species, respectively. The floras of Central Asia and the Caucasus

are also characterized by high endemism (Table 24.5).

Table 24.5 Flora and endemism

For example, the vascular flora of the Krasnodar region (western Northern Caucasus)

includes about 3000 species; about 100 of them are endemics, 63 are paleorelicts, and over

200 are rare. One of the centres of species formation of global significance is located in

this region. However, there are no protected areas with a strict protection regime. There

are a number of large nature reserves protecting the unique flora in two other regions,

the Altay mountains and the Far East, which also feature a high level of plant diversity.

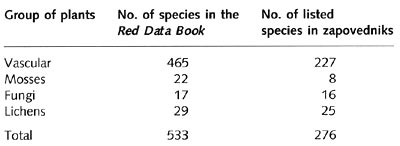

The Red Data Book (1995) lists 533 plant species and only about 50 per cent of them are

protected in zapovedniks (Table 24.6).

Table 24.6 Representation of the Red Data Book (1988) plant species in

the Russian zapovedniks

However, all relicts and endemics are protected. Protection and conservation are

carried out at both the national and regional level. Regional initiatives are extremely

important because species are often exposed to local economic activities and although they

do not require protection nationwide, locally they need to be conserved. Many more plant

species are included in the regional Red Data Books.

Fauna

The fauna of Northern Eurasia has been comprehensively studied and many publications

are dedicated to it (Flint, 1995; Stepanyan, 1990; Borkin and Darevsky, 1987). The

diversity of fauna in a region is controlled by the diversity of natural landscapes. The

fauna of the polar deserts on the Arctic islands comprises two or three mammal species but

there are relatively many bird species associated with the sea. In contrast, the Central

Asian deserts have a poor avifauna while their reptilian and mammal faunas are rich. In

common with the vegetation the fauna of Northern Eurasia has a relatively low endemism

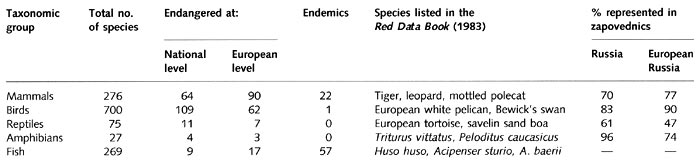

(Table 24.7).

Table 24.7 Characteristics of Russia's fauna and its representation in

zapovedniks

Northern Eurasia cannot be described as a region rich in mammal species. Mammals, the

best investigated group of animals, include 320 species or 7 per cent of the global total.

The best represented is the order of Rodentia. Similarly to plants, the highest diversity

of mammals is found in the Caucasus, the mountains of Southern Siberia, and the Far East.

A quarter of all mammal species is listed in the national Red Data Book (1995). Ninety

mammal species, a third of the total, are in danger of extinction in the European

territory; 39 species, including the tiger and various species of whales, are endangered

at a global level.

An inventory of wildlife species, conserved in the Russian zapovedniks, is now being

made and the preliminary results show that 175 mammal species (70 per cent of Russia's

mammal fauna excluding whales) are protected (Table 24.7). Mammals are clearly

under-represented in nature reserves with 30 per cent of endangered mammal species not

being protected (Krever, 1988).

Avifauna comprises 732 species or 8 per cent of its global number. Most diverse is the

order Passeriformis, which is supported by the vast forests of the region, and

Charadriiformis and Anseriformis, whose abundance is due to the wide occurrence of

wetlands. Fifteen per cent of bird species are listed in the Russian Red Data Book and 9

per cent are rare at the European level such as, for example, falcons. Thirty species are

listed by the IUCN Red Data Book including Dalmatian pelican, Oriental stork, and the

Siberian white crane (Stepanyan, 1990). Birds are well represented in protected areas

although unprotected lands also feature a large number of rare species (Krever, 1988). The

status of Anseriformes populations in tundra, forest-tundra, and steppes, the birds of

prey in steppes and semi-deserts, and cranes in Eastern Siberia and the Far East are a

matter of concern. The Siberian white crane, whose numbers are limited to probably about

400 worldwide (Amirkhanov, 1997), nests only in northern Sakha-Yakutia. However, no

specific nature reserve has been set up in its breeding area.

The reptilian fauna of most of Northern Eurasia is poor because of the severe climatic

conditions. The centre of reptilian diversity is the Central Asian deserts: Karakum and

Kyzylkum. About 15 per cent of reptilian species are rare and endangered at the FSU level

and over 60 per cent of reptile species are conserved in nature reserves. On the European

and global level, the status of the European tortoise population is severe. Many species

of snakes are commercially valuable because their venom is used for medicinal purposes

(e.g., sand viper venom). Recently, illegal trade and smuggling of tortoises and snakes

from Northern Eurasia has increased.

The amphibian fauna of the region is extremely poor. Russia contains as little as 0.6

per cent of the global diversity and there are no endemics. Almost all species listed in

the Russian Red Data Book are protected in nature reserves (Table 24.7). Three species

(Triturus vittatus, Bufo calamita, and Pelodytes caucasicus) are under threat at the

European level.

Unlike mammals and birds, the fish fauna of Northern Eurasia is relatively poorly

studied. It constitutes only 3 per cent of the global diversity. However, there are many

endemics among the fresh-water species, especially in Lake Baikal and in the rivers of the

Amur basin. There are 268 fresh-water species, and the outer seas of Northern Eurasia

contains no less than 400 species. The Red Data Book of Russia lists nine taxa, or 4 per

cent of inland water fauna, with three species (Atlantic and Amur sturgeon, and sheepftsh)

listed by the IUCN. The current status of many species and populations is alarming. Water

pollution, the construction of dams and irrigation systems, excessive commercial fishing,

and poaching have reduced the stock. Badly affected are the fish faunas of the Aral Sea

and the rivers draining its basin, the Volga, Kama, Ural, and the lower course of the Ob.

The major part of the world reserves of sturgeon, salmon, and carp is concentrated in

Russia and it is populations of these species that have been reduced. The sturgeon, which

is the source of caviar, is a particularly important case. The combined effect of poaching

and of the Volga hydroelectric dams has caused a steady decline in the sturgeon catch

which dropped from about 40 000 tonnes at the beginning of the 20th century to as little

as 11 000 in the 1970s (Pryde, 1991). Efforts have been made to restore the population of

sturgeon, including assisted passage upstream to the spawning grounds, constructing

sturgeon farms, and cross-breeding to produce larger and more stable harvests of this

fish. Nevertheless, the problems of degraded habitats and widespread poaching remain.

Poaching has increased dramatically since the collapse of the Soviet Union and currently

the worldwide ban on the export of caviar from Russia, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan is

being discussed as a measure of combating poaching.

Game Animals

For most peoples of Northern Eurasia, hunting was or remains a traditional activity. It

has a long history and has always been relatively well regulated. However, throughout

history rare, endangered or even now extinct species were subject to commercial

exploitation or sport hunting either through the lack of knowledge and gaps in regulations

or because of poaching. In the past centuries, auroch and tarpan, and in the 20th century

the European bison disappeared from Russia and the Ukraine through overhunting. The latter

was later restored in protected areas (Plate 24.1). Central Asia and the Caucasus have

been depleted of the Turanian tiger, leopard, cheetah, and also a number of ungulates.

Plate 24.1 European bison. Three zapovedniks, Oksky, Bieloweza Puszcza,

and Kavkazsky, contributed to restoration efforts of this animal

(photo: courtesy of Dr M. Glazov, Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Science)

At present, most commercial hunting occurs in Russia. It has vast and diverse hunting

lands and a large stock of game animals. The hunting lands, designated for both commercial

and sport hunting, occupy over 16 million km2 in Russia and 5 million km2

in other republics of the FSU. About 60 mammal and 70 bird species are listed as hunting

game. The Russian State Service for Game Animal Registration evaluates the status of game

fauna each year and sets up hunting limits according to the forecast of stock (Lomanov et

al., 1996). Usually, only between 10 per cent and 40 per cent of game is exploited

commercially each year. The problem, however, is illegal hunting. Although most countries

of the FSU have a well-drafted legislation to protect wildlife and traditionally much

effort has been invested in the implementation of hunting laws and regulations, poaching

remains as common now as it was decades and centuries ago. At present, underfunding and

insufficient personnel make many measures, aimed at both control of poaching and game

management, inefficient. Poor living standards, especially among indigenous and rural

populations, and high prices offered for rare species and for hunting make illegal hunting

more widespread. In Russia alone, up to 50 000 cases of poaching are registered annually

(State Report, 1997).

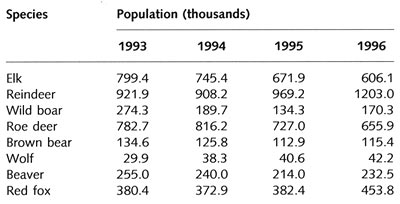

In addition to the mammal species listed in Table 24.8, allowed for commercial hunting

are reindeer, arctic fox, red fox, marten, Siberian weasel, and Eurasian otter. Marine

mammals are hunted in the northern seas, in the Pacific and in the Caspian Sea. All these

species are important both commercially and for the indigenous economies. The largest

group of game birds are waterfowl. In Russia, up to 90 million birds (out of which about

75 million are ducks) are allowed for hunting with no more than 10 per cent being killed.

Western Siberia, the Far East, the wintering sites around the Caspian Sea, the lakes of

Kazakhstan, and Central Asia are the major hunting regions. Species of grouse are another

commercially exploited group and between 4 and 5 million are shot each year (State Report,

1996). There are various measures designed to maintain the population of these birds.

These measures include a ban on hunting during the breeding season, protection of birds

from predators in zakazniks, and breeding in farms.

Game populations vary between years depending on harvests of the previous season,

availability of forage, and climatic factors (Table 24.8).

Table 24.8 Population of game animals in Russia

Some interesting variability has been observed in the stock of elk. In the past

centuries, this species was rare and its population began to grow only with an increase in

forest clearings when the forest regrowth provided forage (Salix and Populus tremula).

During the early 1990s, the population of elk in Russia has declined by 25 per cent, with

the most drastic reduction being observed in European Russia (Lomanov et al., 1996).

However, hunting was also declining. In the 1980s, between 70 000 and 80 000 animals were

killed annually, while in the 1990s hunting was limited to between 30 000 and 50 000. It

is likely that changes in the stock of elk are linked to climatic variability rather than

to commercial use and poaching. The stocks of wild boar and roe deer have been declining

in Russia although their numbers remain high in the Ukraine and Georgia, and the Baltic

states.

One of the most popular animals for hunting, traditionally associated with Russia, is

the brown bear. In the 18th and 19th centuries, these bears occurred in densely populated

areas, in the vicinity of Moscow and further south, in the Tula and Orel regions (Kirikov,

1966). Bear hunting was extremely popular, as were its trophies and trophy prices were

enormous. At the beginning of the 20th century, in Central Russia bear hunters were paid

in silver, payments being equal to one-twentieth of the animal's weight, which was a

fortune by the standards of the time (Pazhetnov, 1993). Overhunting and a reduction in

habitats caused by the development of agriculture limited the distribution of the brown

bear. Its population in Central Russia declined until the end of 1960s when a temporary

ban on bear hunting in the region was imposed (Pazhetnov, 1993). In 1996, there were about

115 000 bears in Russia. Annually, about 3000 are shot mainly in the Arkhangelsk, Vologda,

Perm and Yekaterinburg regions, in Kamchatka, and the Khabarovsk region. The trophy fee, a

hunter must pay to shoot a bear, varies between US$50 and US$500.

Although lynx is rare in Central and Western Europe, in Russia, there are currently

about 30 000 individuals and about 2000 are legally shot each year. In European Russia,

the highest density of the lynx population occurs in the north in the Vologda region where

it reaches 10-15 per 1000 km2. In the central part of European Russia, the lynx

population is about 4-5 per 1000 km2. Similar to other animals, the population

of lynx varies year to year and is now declining, particularly in western regions.

One of the most common game animals is wolf. Its distribution encompasses most natural

zones and has not changed in historic times. The population of wolves is rising; between

1991 and 1996, it has increased from 27 000 to 42 000. It is considered a dangerous animal

which harms cattle and, being a very successful predator, wildlife. To control the wolf

population and the damage inflicted, in many areas hunting wolf is encouraged.

Across the FSU, a system of protected areas (hunting zakazniks) has been established

for the conservation of game species and their habitats but with the purpose of providing

the opportunity for sport hunting. These zakazniks play a very important role in the

conservation and reproduction of game fauna. There are 1064 such areas in Russia covering

over 525 thousand km2, 20 in the Ukraine, 18 in Kyrgyzstan, 15 in Tajikistan,

10 in Azerbaijan, 13 in Kazakhstan, and 13 in Belarus (Borisov et al., 1985; Amirkhanov,

1997). There is also a network of game farms that feed and protect game animals during the

breeding period.

<<< Restoration of Primary Vegetation

in Damaged Ecosystems | Environmental Problems Index | International Conventions >>>

Contents of the Nature Protection and

Conservation section:

Other sections of Environmental Problems of Nortern Eurasia:

|

|