Please put an active hyperlink to our site (www.rusnature.info) when you copy the materials from this page

Environmental problems of Northern Eurasia

Nature Protection and Conservation

<<< History of Conservation: Efforts

and Attitudes | Environmental Problems Index | Geography of Biodiversity and Human Impact >>>

Territorial Forms of Nature Protection

There are different categories of protected areas with a diversity of designations:

zapovednik, zakaznik, national park, nature monuments, and customary nature use areas

(Table 24.1). At the end of 1997, the Russian system of protected areas included 95

zapovedniks, 32 national parks, over 1600 state zakazniks, and about 8000 nature monuments

including 29 monuments of national importance.

See descriptions and images of Russian Zapovedniks and National parks in a special section of

our site.

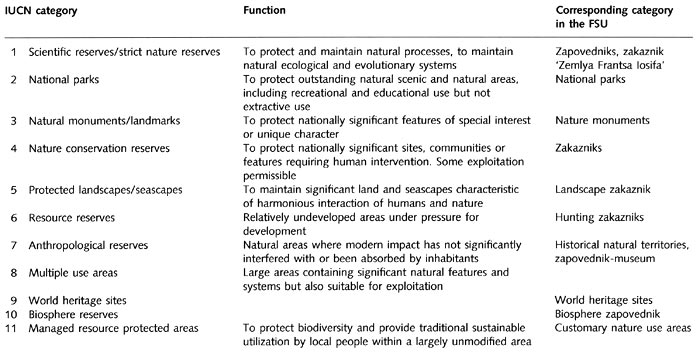

Table 24.1 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural

Resources (IUCN) reserve categories and reserve categories used in the FSU

Zapovedniks

See descriptions and images of Russian Zapovedniks and National parks in a special section of

our site.

State zapovedniks are the strictest territorial form of nature protection (Table 24.1).

Zapovedniks are areas permanently withdrawn from economic use. They also include academic

research facilities for investigation of ecology, conservation, and monitoring of

landscape and biological diversity. Academic orientation is a distinguishing feature of

zapovedniks, which makes them superior to nature reserves in many other countries.

Traditionally, research stations owned by universities and national Academies of Science,

are attached to zapovedniks. Continuous observation of protected populations and research

on the dynamics of vegetation communities are carried out, thus creating a unique network

of research sites with 30-60 year-long data records on ecosystems and biota.

The first nature reserve, Askanya Nova, was established in the Ukraine in 1874. The

history of Russian zapovedniks dates back to 1916 when Barguzinsky zapovednik was

established near Lake Baikal to protect sable and Kedrovaya Pad zapovednik was set up in

the southern Far East to conserve the rich biodiversity of the Far Eastern forests. Since

then, the development of the zapovednik system has been following the physical

geographical and biogeographical principle that every bio-geographical region should have

a zapovednik (Tishkov, 1991, 1993, 1995; Shtilmark, 1996). Although successful, the

history of zapovedniks in the FSU is not trouble-free. For two decades, between the late

1930s and 1950s, conservation areas were considered by many Soviet officials as the

alienation of land which otherwise could be used for industrial and agricultural

development. Nature was treated as a resource that should be exploited and therefore

conservation was viewed as an obstacle to the established economic priorities. In 1951, at

a peak of the anti-preservation campaign, the number of zapovedniks was reduced by 70 per

cent and their area by 80 per cent (Pryde, 1991). Restoration of the system began in the

late 1950s, following Stalin's death and a relative democratization of the Soviet regime,

but not until the mid-1980s was the area previously occupied by nature reserves again

achieved. In most countries of the FSU, zapovedniks remain the main territorial form of

conservation, although Belarus, the Ukraine, and Baltic states now focus on the creation

of national and natural parks. The break-up of the Soviet Union, economic transformation,

decentralization of power and, in some regions, deteriorating socio-economic conditions

have put many zapovedniks (and other protected areas) under pressure. Poaching and grazing

on protected lands and attempts to use them for development have become common. However,

so far in Russia, Belarus, the Ukraine and Baltic states not a single zapovednik has been

closed. Moreover, six new zapovedniks were established in Russia between 1994 and 1997

(Table 24.2).

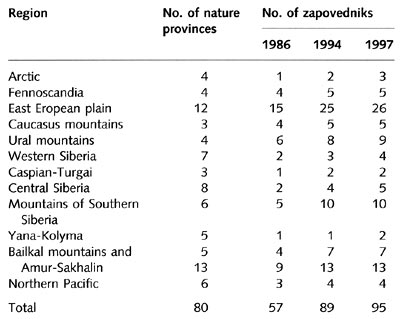

Table 24.2 The distribution of zapovedniks according to the

physical-geographical regions of Russia

Zapovednik territories vary widely from 2-3 km2 (Galichia Gora in Russia and

Ukrainian Steppe in the Ukraine) to 40 000 km2 in remote areas, mainly of

northern Asia (Figures 24.1 and 24.2).

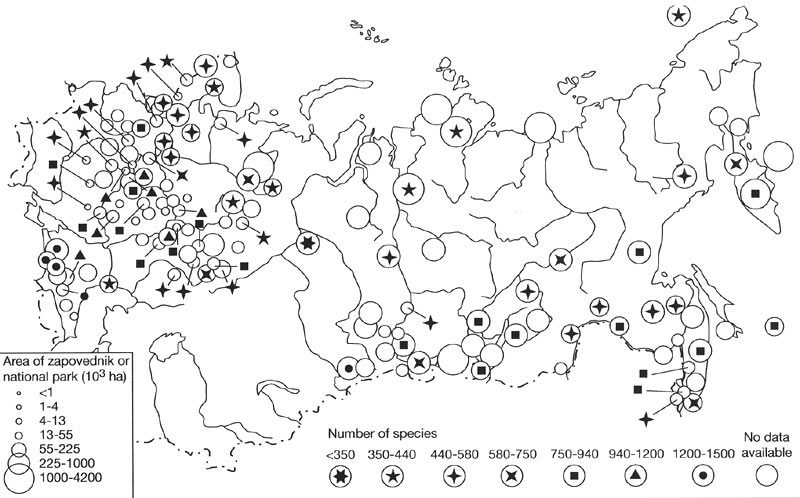

Fig. 24.1 Areas of zapovedniks, national parks, and the number of

protected flora specimens

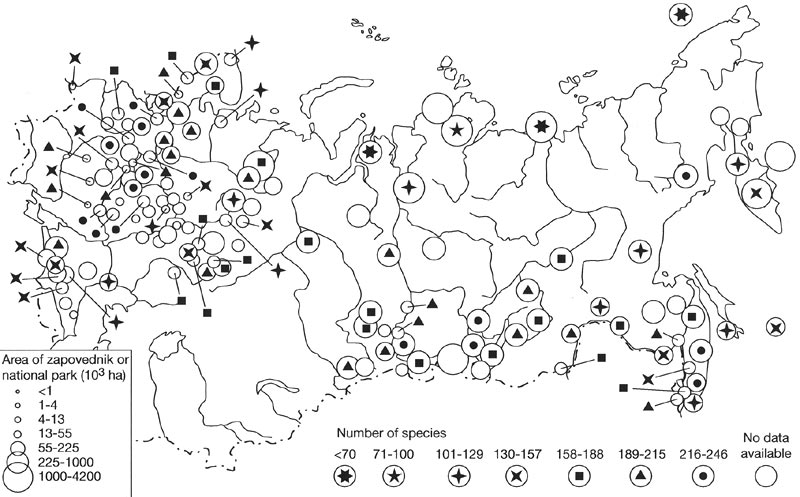

Fig. 24.2 Areas of zapovedniks, national parks, and the number of

protected fauna specimens

Depending on location and size, zapovedniks conserve between 300 and 1500 vascular

plant species which constitute between 30 per cent and 80 per cent of regional floras.

Locations and boundaries of zapovedniks are selected to combine area, representativeness,

and hot spots defined by species-richness, endemism, or distinctiveness. Recently, a

'catchment' principle has been adopted in designing zapovedniks. According to this

principle, a protected area includes the catchment of a stream, river or lake draining the

area. This creates a buffer zone and protects an ecosystem and biota designated for

protection from external impact.

At the end of 1997, there were about 300 zapovedniks in the FSU. Russia accommodates 95

of those, employing over 5000 full-time personnel, mainly academic staff, and guards. In

Russia, zapovedniks occupy a vast area of over 310 000 km2 with the terrestrial

zapovedniks accounting for approximately 262 000 km2 (State Report, 1997).

Although impressive, this system contains gaps. In Russia, zapovedniks cover only a modest

1.5 per cent of the total territory. The distribution of zapovedniks and land covered

across the FSU is uneven. For example, in northern Taymyr, zapovedniks occupy 10 per cent

of the total area, while in some steppe regions, which contain high biodiversity

threatened by overdevelopment, only 0.1 per cent of the territory is covered. Tishkov

(1995) evaluated the regional coverage with respect to zapovedniks in Russia and concluded

that many areas, especially in the biomes of polar deserts, forest-tundra, larch open

forests, steppes, and semi-deserts are under-represented (Figures 24.1 and 24.2; Table

24.2).

National Parks

See descriptions and images of Russian Zapovedniks and National parks in a special section of

our site.

National parks play an important role in the conservation of biodiversity, protection

of sites of high aesthetic or historical value, and are intended for recreation (Table

24.1 above). Because national parks have a conservation function, crucial to their

performance is a zone with a strict conservation regime. Such zones occupy between 7 per

cent and 44 per cent of the total park territory (National Parks of Russia, 1997).

Although the first suggestions to create national parks in Northern Eurasia date back

to the beginning of the 20th century, further conservation efforts focused on zapovedniks

and it was not until the 1970s that the first national parks were established in Estonia

(Lakheemaasky) and Latvia (Gauya). The first Russian national parks, Losiny Ostrov within

the Moscow urban area and Sochinsky on the Black Sea coast, were founded in 1983.

Currently, there are 32 national parks in Russia with a total area of 66 500 km2

(0.4 per cent of the country's territory). The parks vary in size from 66 km2

(Kurshskaya Kosa in the Kaliningrad region) to 19 000 km2 (Yugyd Va in the Komi

Republic).

National parks complement conservation work carried out in zapovedniks. For example,

there are no zapovedniks on the Russian coast of the Black Sea and the conservation

functions fall with the Sochinsky national park which preserves habitats of European

tortoise and also more than thirty plant species listed in the Red Data Book (1988). The

Valday national park protects the only large forest massif between the two largest Russian

cities, Moscow and St. Petersburg, which harbours large game, mainly brown bears.

Zakazniks

Zakazniks are areas withdrawn for either permanent or temporary protection. This form

of nature protection usually corresponds to category 4 of the IUCN classification (Table

24.1), although some zakazniks do not meet the category 4 criteria and should be

attributed to categories 6 or 7. On the other hand, the largest zakaznik, Zemlia Frantsa

losifa which was founded in 1994 on Franz Josef Land and occupies 42 000 km2,

is regarded as a category 1 protected area. Zakazniks are aimed at protecting one or many

components of the natural environment. Their status can be national, republican, regional

or local. The key function of zakazniks is animal and game conservation, and breeding and

often they integrate conservation with hunting. Zakazniks also protect rare species

including 21 mammal and 68 bird species listed in the Red Data Book (1988).

At the end of 1997, there were more than 1600 zakazniks in Russia with a total area of

more than 600 000 km2 (State Report, 1997). Among those, 66 are of national

importance. Another 19 zakazniks conserve wetlands of international significance under the

1971 Ramsar Convention.

Nature Monuments

Nature monuments are relatively small territories or individual nature objects which

are conserved without land withdrawal by the decision of local authorities. Unique

geological outcrops, habitats of rare plants or animals, a wood, a lake or an ancient tree

can be given the status of a nature monument. This form of protection was initiated in the

1960s and proved an efficient and flexible way to realize local initiatives for

small-scale conservation. It is especially popular in the regions where non-governmental

organizations are actively involved in conservation. For example, in the Komi Republic

there are about 500 nature monuments. However, in those regions where environmental

awareness of the public and local authorities is not strong, nature monuments come under

particular pressure. At the end of 1997, there were about 8000 nature monuments in Russia.

Of these 29 are of national importance and mainly protect small woodlands.

Customary Nature Use Areas

Customary nature use areas are a comparatively new form of nature protection in the

regions of residence of indigenous communities in the Russian north, Siberia, and the Far

East. They are created by the decision of local authorities and have been established in

the Khabarovsk region, on the Yamal and Taymyr peninsulas. The development of these areas

is limited so that indigenous peoples can maintain their traditional occupations such as

hunting, fishing, and trapping. This form of nature protection does not create the

conflict that often exists between conservation (i.e., ban on hunting and fishing in

nature reserves) and traditional economies.

<<< History of Conservation: Efforts

and Attitudes | Environmental Problems Index | Geography of Biodiversity and Human Impact >>>

Contents of the Nature Protection and

Conservation section:

Other sections of Environmental Problems of Nortern Eurasia:

|

|