Please put an active hyperlink to our site (www.rusnature.info) when you copy the materials from this page

Environmental problems of Northern Eurasia

Air Pollution

<<< Case Study. Air Pollution in the

Arctic: A Hazy Perspective | Environmental Problems Index |

Conclusions >>>

Case Study. Moscow: From Plan to Market in a Private Car

As recent studies have shown, environmental performance during the period of economic

transition has been regionally differentiated according to a range of interrelated factors

such as individual regions' preexisting socioeconomic structure, their resource base, and

attractiveness to foreign capital and the attitude of the regional leadership towards the

environment (Zamparutti and Gillespie, 2000). Moscow is a centre of reformist strategy, a

position it has secured as a result of a reformist leadership, the involvement of

international agencies in economic transformation, and an industrial structure which has

proved to be adaptable, in parts, to conversion and restructuring. If environmental

improvement associated with transition were to figure anywhere in the FSU, it would be

reasonable to expect it to do so in a high-profile city such as Moscow.

It has already been mentioned that although the largest, Moscow has never been the most

polluted city in the FSU. The first attempts to improve air quality in Moscow date back to

the 1960s when more than 600 polluting factories were closed down. Later, heating was

centralized which allowed the elimination of numerous low-level sources of pollution

universally known as major contributors to air pollution episodes. Subsequently, power and

heating plants have been converted to burn natural gas (a cleaner and cheaper fuel) which

at present accounts for 95 per cent of fuel burnt in the city (pp. above). Following this

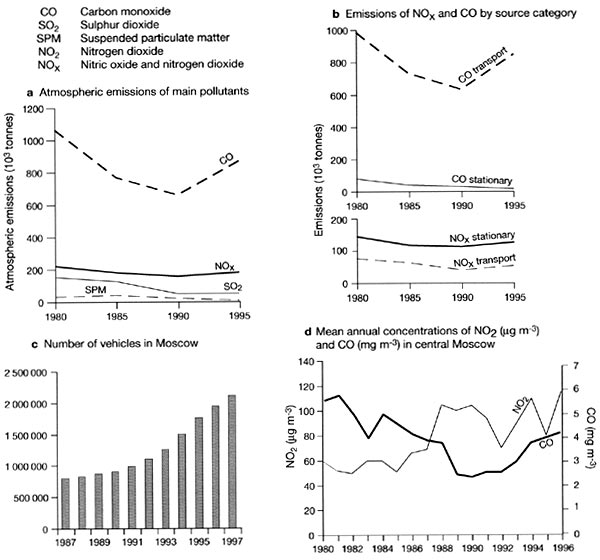

transfer, emissions of SO2 and SPM have declined dramatically (Figure 21.11a).

Fig. 21.11 Characteristics of air pollution in Moscow

Power generation is still the main source of NOX in Moscow, contributing over 60 per

cent of total NOX emissions (Shahgedanova et al., 1999) and in order to reduce pollution

by NOX, low burners have been introduced extensively and successfully employing mainly

indigenous technologies, although international cooperation also played a part (Hill,

1997, 2000). Thus a reduction in pollution from stationary sources has been achieved and,

with regard to power generation, economic reforms and the policy of openness may encourage

the 'decoupling' between production and air pollution emissions in the future. While

energy efficiency has improved, the growth of car ownership associated with the transition

presents a major threat to the urban environment. A steady reduction in CO and NOX

vehicular emissions was observed in the city between 1980 and 1988, despite an increase in

car numbers following the introduction of newer engine designs, growth of diesel fuel

consumption and changes in driving patterns. However, since 1990 the number of cars has

increased dramatically leading to the growth of vehicular CO and NOX emissions and

concentrations (Figure 21.11). The vehicles are often old and poorly maintained; the

quality of fuels is also low in comparison with those used in the West (although the

widespread use of compressed natural gas in Moscow is undoutably beneficial). So far,

neither the federal environmental agencies nor the Moscow City Council has developed a

coherent transport strategy for the city. The Russian Law on Air Quality is aimed at power

generating and industrial sources (Shahgedanova and Burt, 1993), which in previous years

were the major sources of pollution across the country. In the absence of controls,

Moscow, as so many other European cities, now faces a serious problem with regard to

vehicular pollution.

<<< Case Study. Air Pollution in the

Arctic: A Hazy Perspective | Environmental Problems Index |

Conclusions >>>

Contents of the Air Pollution section:

Other sections of Environmental Problems of Nortern Eurasia:

|

|