Please put an active hyperlink to our site (www.rusnature.info) when you copy the materials from this page

Environmental problems of Northern Eurasia

Air Pollution

<<< Air Pollution before 1990:

Industry and Power Generation | Environmental Problems Index

| Air Pollution after 1990: Environment in Transition

>>>

Controlling Air Quality: Cleaner Fuels

The FSU has often been accused of neglecting the environment and sacrificing

environmental concerns to production quotas (Ziegler, 1987; Jancar, 1987; Pryde, 1991;

Petersen, 1993). This can be explained but cannot be disputed. The FSU emitted more

pollution than Western countries relative to GDP (Bond, 1991). However, policies aimed at

the reduction of air pollution have been pursued and while some were controversial, others

proved successful. A very significant positive step was the upgrading of outdated

industrial plants (many used equipment dating back to the 1930s or acquired from Germany

and its allies at the end of the Second World War) and removal of heavy industry away from

large administrative cities, which continued since the 1970s albeit slowly. Among the

controversial measures of air pollution reduction is the so-called 'high-stack policy'

adopted by many industrial countries in the 1970s: in order to disperse pollutants from

chimneys more efficiently, 100-200 m tall chimneys were constructed. A shift away from

domestic solid fuels towards centralized power generation and heating have certainly

helped to improve urban air quality and it should be facilitated in towns of the Asiatic

part of the region where domestic heating is still an important source of pollution

including toxic pollution. However, tall chimneys contribute significantly to the

acidification of precipitation and ecosystems downwind and need to be combined with other

more active pollution control techniques. Post-combustion treatment of effluent gases was

required by law, however, in the early 1980s as much as 25-40 per cent of all installed

gas scrubbers and dust collectors were ineffective or inoperable and the expenditure on

air pollution abatement between 1976 and 1988 was a fraction of that in the United States

(Pryde, 1991).

Most significant reductions of acid emissions have been achieved through switching of

fuels from coal and oil to natural gas. The combustion of natural gas, often described as

the most environmentally friendly fossil fuel, generates only negligible amounts of SPM,

sulphur (hydrogen sulphide is removed from natural gases.) and aromatic hydrocarbons such

as benzo(cx)pyrene. Natural gas contains nitrogen in a form that leads to NOX emissions

that are 30 per cent lower than those for oil and 50 per cent for coal (Hill, 1997). As an

additional benefit, natural gas has a high hydrogen to carbon ratio and produces 54 per

cent of CO2 emissions of hard coal per unit of heat generated and its use may

help to curtail global warming (Hill, 1999, 2000).

In 1955, the proportion of natural gas in the total USSR fuel consumption was 2.4 per

cent; in 1987 it was 25 per cent. With regard to power generation, coal was the main type

of fuel accounting for 47 per cent of power plants' fuel balance nationwide in 1970; heavy

fuel oil accounted for 23 per cent and natural gas for 24 per cent (Sagers, 1990). The

production of oil peaked in the 1970s and its proportion in the fuel balance increased by

1980. However, in following years, the emphasis was firmly on the introduction of natural

gas and its proportion in the fuel balance increased to 50 per cent in 1990, although the

absolute consumption of coal did not change significantly. The shift to gas was especially

large in the European territory where absolute consumption of coal also declined. Already

in 1985, natural gas accounted for 80 per cent of fuel burnt by power plants in Tatarstan;

in Moscow, its share increased from 62 per cent in 1980 to 8 7 per cent in 1990 and

further to 95 per cent in 1995 (Shahgedanova and Burt, 1994; Hill, 2000). In Siberia, coal

remained the main fuel but the main supplies were expected to be from the Kansk-Achinsk

region where coal has a sulphur content of 0.2-0.4 per cent which compares favourably with

the typical Donetsk anthracite containing 1.7 per cent of sulphur. In Kazakhstan its

consumption has increased as the Karaganda and FJdbastuz coal basins have been developed.

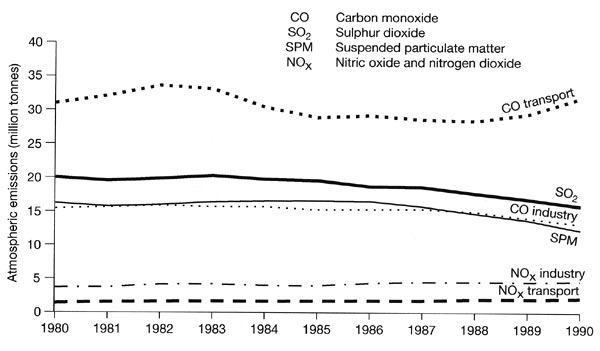

Fuel switching from coal and oil to natural gas had undoubtedly led to a reduction in

emissions of SPM and SO2 prior to 1990 (Figure 21.4).

Fig. 21.4 Atmospheric emissions in the former Soviet Union

Russia has almost unlimited supplies of natural gas and its use will most definitely

continue to grow for price reasons, especially in the European part of the FSU. An

increase is feasible in the Far East when the Sakhalin deposits are fully exploited.

However, it is likely that coal will remain the main fuel in Siberia where major

coalfields are located and there is scope for fuel cleaning and the use of cleaner post-

and in-combustion technologies in this region. These are comprehensively reviewed by Hill

(1997, 1999, 2000).

<<< Air Pollution before 1990:

Industry and Power Generation | Environmental Problems Index

| Air Pollution after 1990: Environment in Transition

>>>

Contents of the Air Pollution section:

Other sections of Environmental Problems of Nortern Eurasia:

|

|